GA.BO.SIA

Amartey Golding

Preview

Saturday 10th June 6-8pm

Exhibition 10th June to 8th July 2017

Amartey Golding on GABOSIA

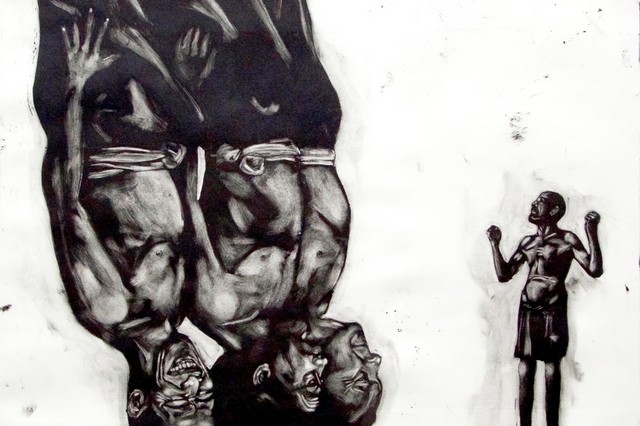

‘Gabosia is an ongoing series of drypoint prints that I started in 2013 after revisiting the mysterious circumstances around my father’s death. The series explores how storytelling is used instinctively as a tool to provide solace and answers. The prints narrate a complex and fantastical fable with characters made up of google-derived imagery. It acknowledges how fiction is able to steer reality and offers visceral justifications for my father’s death’.

The Myth Maker by Kevin Jones

Myth is a slippery, shifting thing. Seemingly anything can happen in mythical tales. Yet they are governed by a corpus of patterns and tropes, common across all cultures. Myth is allegedly archaic. Yet it hides in the billboards and TV spots of our mass-mediatised here-and-now. Many are the minds who have grappled with myth. Sigmund Freud linked it to repressed desires. Psychiatrist C.G. Jung had it dwelling in our collective unconscious. Revered mythologist Joseph Campbell uncovered myth’s surprising consistency across cultures, while French semiotician Roland Barthes examined how it delivered specific – and not entirely innocent – messages. But the many minds agree on one thing: myth represents our psyche; it expresses the unconscious mind. What remains mysterious, though, is the articulation of myth – the complex apparatus of mythmaking itself.

Amartey Golding is a mythmaker. To call him a storyteller would be to underestimate his sensitivity to myth’s insidious nature. Yes, his stories amaze with their myriad of fabulous characters sprung from the recesses of his rich imagination. But his visual work taps into the essence of myth as an alternative language, as a means of confronting and understanding life. In Amartey’s hands, myth becomes the ultimate cultural bridge: African, Greek and Japanese referents are folded into a pop-culture-laden visual mix that overrides geographies and ethnicities. If myth is timeless, Amartey’s work manages to indicate both where we have come from and where we are headed.

Amartey does not update myths as much as he reinvents them for our contemporary culture. Perhaps the cornerstone of this endeavour is the character Gabos. Culled from the prison-speak unveiled by Louis Theroux’s 2011 documentary Miami Mega Jail, the name is an acronym for Game Ain’t Based on Sympathy, the inmates’ survivalist, every-man-for-himself mantra. Gabos is a darkly dual character. His weighty corpulence in the print Freudian Gabos harks back to a Lucien Freud nude, the title slyly referencing both portraitist and psychiatrist, threading up the mythical link. Gabos is key to the myth of the Seed Collector and the layered, twisting offshoot stories of agrarian villagers and their sacrifices – a tale that was somehow cathartic for the artist to imagine, further to his father’s death. In the large-scale print depicting the male villagers’ decision to perform their sacrifice, The discussion of Mihael’s Epic, we stand firmly in the realm of mythological time: portent is freeze-framed, as if on an urn.

In spite of this classical flourish, Amartey’s work is deeply contemporary. The ebb and flow of popular culture brush snippets of internet-gleaned imagery across the prints of this revamped mythical world. Among the Seed Collector’s village cohorts we spot the faces of Desmond Tutu, Marlon Brando and James Baldwin. Elsewhere, Bart Simpson and the Family Guy face off like clashing Titans. The so-called Woolwich killer peers out at us like a modern Oedipus, his hands bloodied, his fatality sealed. Even Obama appears in this latter work, his detached head chuckling in the corner, like some abridged and ambivalent Greek chorus, ironising on irreversible doom.

Like many a mythic hero, Amartey finds himself at a crossroads. Until now, he favoured intricate draughtsmanship, rendered primarily in tricky charcoal. Compared to the multi-layering of his newly imagined world and its attendant messaging, previous imagery seemed more geared towards contemplation – he was nudging viewers to make up a story, rather than letting his seep in. Encounters with his pre-Tashkeel residency were rousing: each piece seemed to bare it soul in one fell swoop. Now, his works hint more than reveal; they are “received” rather than read.

Most importantly, Amartey capitalised on the yearlong residency at Tashkeel to change media: from his signature charcoal, he moved on to dry-point printmaking. This shift was at once a homecoming and an initiation. Homecoming firstly because his mother and grandfathers were all printmakers. Secondly, he has seemingly “found” himself in the technique. Although charcoal dominated his previous work, it was, surprisingly, almost consistently an angular, structured application, with minimal smudging. On Tashkeel’s large press, however, he is experimenting with rich, blurred lines and inky shadow-play – results that would conceivably have attracted him to charcoal in the first place. The initiation lies in the gradual mastery of the challenges of dry-point printmaking – a journey whose completion augurs a major new phase in his artistic career.

Mythmaking and printmaking share a love of perseverance. Tales are told and retold, their words embellished, their sentences honed, their storylines fine-tuned. Perfecting a yarn is a repetitive, laborious undertaking: characters are drawn out and enriched after much trial and error, plots thicken as new twists and turns are added or edited away. The steady minutia that contributes to making a story both gripping and seamless is analogous to the conscientious scratching and cutting of printmaking. The plate is meticulously, repeatedly fashioned so that each small incision somehow endows the whole with a new impression. Printmaking thrives on unpredictability: tiny details – paper soaking times, needle choice, pressure – alter outcome considerably. Unlike drawing or painting, a print cannot truly be grasped as it is taking shape, but only once the process is complete, and the result revealed. Like mythmaking, it is both painstaking and obscure.

The works in GABOSIA seem like glimpses into a much larger body of work, as if they were morsels of wider narratives, plucked from broader cycles. The fact that these prints constitute the bulk of Amartey’s latest work is testament to the promise in his new path. “I am trying to write mythologies for the new nomads,” he confessed, “Mythologies that are not linked to a given geographical space or cultural influence. For a transient and interconnected globalized generation, where cultural lines are blurred.” Revelling in the flux of our contemporary world, Amartey embraces shifting imagery. Being a mythmaker, then, is less about pinning down myth for all to see, than about recognizing that we never really can.